Originally published on Spotlight on Poverty and Opportunity

Spotlight on Poverty and Opportunity about keeping children safe during COVID-19 and protecting against child abuse.

When Oklahoma’s schools and daycare centers shuttered in March to slow the spread of COVID-19, toddlers to teens saw their in-person education experience replaced by virtual learning and homeschooling. The state’s child abuse hotline also saw a 50 percent drop in calls, which child welfare professionals there attribute to the reduced contact that teachers and carers had with their charges.

Now that school’s out and back-to-school arrangements for the fall are uncertain, Oklahoma — like other states across the nation — faces the same challenge: how do you keep children and teens safe from abuse when the safety nets of daycare and school disappear?

Under normal circumstances, teachers, daycare staff and after-school activity leaders are key adults in children’s lives who can act as ‘reporters’ of suspected child abuse and neglect. They serve as the eyes and ears of child safety in the nursery, classroom, or on the athletic field.

COVID-19 changed all this, replacing classroom contact with Zoom video calls and email check-ins. Aftercare activities were canceled. Sports were shut down.

This widespread loss of in-person contact with children and young people immediately led to dramatic drops in reporting across the country. According to one report in April, calls to Washington state’s child abuse hotline went down about 50%, while Montana and Louisiana reported about a 45% reduction since schools closed in March. Arizona’s calls were down a third compared with previous weeks. “That means many children are suffering in silence,” Darren DaRonco, spokesman for the Arizona Department of Child Safety, told the Associated Press.

Child welfare system experts warn that the current system of detecting abuse and neglect is rendered “almost completely powerless” during pandemic restrictions. “The child protection system really depends on reporting by professionals. And now professionals are seeing [children] much less, that’s a very fundamental problem. The single biggest problem,” says Ron Haskins, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and co-director of its Center on Children and Families.

Oklahoma has the highest percentage of adverse childhood experiences in the country, with 28.5% of children age 0-17 experiencing two or more stressful or traumatic events that may have a lasting impact on their health and well-being. The latest data for the state shows that 13,125 children are neglected and 1,379 abused each year.

Maura Guten is president and CEO of Child Abuse Network, Tulsa’s children’s advocacy center which brings multiple agencies such as doctors and police under one roof to investigate child abuse. She says shelter-in-place arrangements have exacerbated Oklahoma’s already concerning child welfare situation.

“We’re the acute response… and these are some of the worst cases I’ve seen in 20 years,” says Guten. “There is a lot more serious neglect, for example very young children wandering [alone] outside and nobody recognizing that they’re gone for an extended period of time. And we’re seeing a lot more hospitalizations, use of our mobile interviewing equipment, and more emergency interviews in the evening or early morning.”

During a normal summer, CAN sees 40-50 children a week. Guten says lockdown could easily double that workload: “We’re seeing a lot more kids independently seeking services — running away, running for help to a police station or neighbor.”

Family & Children’s Services (FCS) is the largest community mental health center in Oklahoma and provides therapeutic services to victims of child abuse and neglect. Christine Marsh, FCS’s senior director of child abuse and trauma services, says the side effects of COVID-19, such as job losses, financial stress and living in close quarters, have placed an additional burden on families: “People are getting on each other’s nerves, there is high stress and possible depression because of the ongoing isolation,” she says.

“And kids whose parents do have to work are being left unsupervised, or in the hands of people who really aren’t prepared to take care of kids and could cause harm.”

Marsh says FCS therapists have had to adapt their video or telephone interactions with children, for example, if family members are in close proximity: “We’ve worked on code words for kids, so instead of saying, ‘I don’t want to talk about it, my mom’s sitting here’, we set up a code word they can say to mean, ‘Someone’s here and I don’t want to talk about that right now.’”

This response echoes what domestic violence organizations are doing to help victims communicate abuse during COVID-19, such as the Signal for Help gesture launched in April by Women’s Funding Network.

Haskins calls for greater public awareness of the prevalence of child abuse, and for reporting to fall within the purview of everyone in the community and not just professionals. “I think people are aware in maybe an abstract way,” he says. “But it’s about emphasizing to the public not only that there is a problem, but that kids in their own community are undoubtedly being neglected, and in some cases abused.”

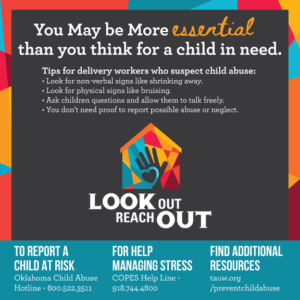

Since May, an awareness campaign in Tulsa has been urging everyone from pizza delivery people to grocery store clerks to help keep young people safe over the summer and beyond. The Look Out, Reach Out campaign calls on the whole community to recognize and report signs of child abuse and neglect, and publicizes the state’s child abuse hotline.

A collaborative project by local non-profits and co-ordinated by Tulsa Area United Way (TAUW), the campaign was launched in May via NBC affiliate KJRH-2 Works For You, in the form of a TV slot aired every Thursday during that month about how to recognize and report abuse and neglect.

On May 29, TAUW and campaign partners Child Abuse Network, Family & Children’s Services (FCS), and The Parent Child Center of Tulsa launched a website, collating the advice and information discussed on the TV slots. From July, flyers promoting the site and helpline will be distributed at sites with high footfall including 81 QuikTrip convenience stores/gas stations, 17 Reasor’s grocery stores, seven Goodwill shops and four Supermercados Morelos outlets in the Tulsa area.

TAUW leveraged pro bono support from its supporter network for the campaign branding, messaging, and execution. Social media including Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, is being used to communicate campaign messages.

Krista Hemme, TAUW’s VP of marketing and communications, says the campaign is aimed at both “the usual abusers” but also parents who never thought they’d be in a situation where they would strike a child. “There is an incredible need to make the community aware of what the warning signs are, prevention, what parents can do, and making people aware of the reporting process — that you can do anonymously.”

Marsh at campaign partner, FCS adds: “If you’re the pizza delivery person that’s going into a home because you’re one of the frontline people now — and you notice something — you can report. It doesn’t hurt to make a report. And it can create a trail of trends even if that report isn’t going to cause an investigation.”

During a regular school year, YWCA El Paso in Texas sees around 2,500 children a week through its after-school programs. But, with schools closed and its programs shuttered, that figure dropped to about 250 children a week during lockdown. Texas saw child abuse reporting reduce significantly since March, yet the numbers of children showing up at emergency rooms with head trauma, bruises and other injuries spiked.

The non-profit applied for and was granted a PPP loan, enabling it to quickly pivot from staff running after-school activities to the YWCA Cares program, checking in with vulnerable families and providing respite care.

Dr. Sylvia Acosta, CEO at YWCA El Paso, says: “We informed every school district in our community and we worked out a way that counselors could refer individuals to us that they felt needed lots of support.”

For example, a 13-year-old girl had not shown up to class since schooling went virtual. YWCA followed up with the family and discovered that the single parent had several other children under the age of 13, including a child with a disability. The 13-year-old had had to step in to help her siblings with homework, meaning she could not show up online for school.

“We were able to provide respite care for three days and also connect the family to long-term childcare funding so they could continue with that,” says Dr. Acosta. “So all the children except for the 13-year-old were out of the house, the parent could take care of the child with the disability, and the 13-year-old could go back to school.”

Staff provides three days of respite care, between 6:30 am and 6:30 pm. This offers parents a chance to take time out, organize household chores, and investigate long-term childcare subsidies. “It allows them to take a step back and allows us to help them find the resources to be successful,” says Dr. Acosta.

While these initiatives are to be welcomed, school professionals worry that many at-risk children still face huge challenges. Melissa Ambrose, school wellness coordinator for Jefferson Union High School District in the San Francisco Bay Area, gives the example of a senior who had been set to leave home — where her parents experience chronic alcoholism and gambling addiction — for college in the fall but now cannot as teaching at her college will now be virtual due to COVID-19 restrictions.

“She’s devastated,” says Ambrose. “She says she can’t bear her house for another year. But she has no choice.”

Ambrose is also concerned about how counselors will see students when schools go back: “None of our offices have six feet of space. How do we see kids privately?” And with no budget for professional development in the coming school year, she is worried that teachers won’t be equipped with the skills they need to keep students safe: “What we really need is for teachers to be trained in trauma-informed practices because they’re going to have way more contact with the kids than we are,” she says. However, union rules stipulate that any training over the summer cannot be mandatory and must be compensated.

Funding is a perennial problem, says Haskins at Brookings, who hopes for more federal dollars for child welfare services: “That would be something the federal government could do if it was worried about this problem — figure out a way [to give] more money to the states to conduct these programs, to make more home visits, to purchase more protection for the workers who are having to visit the homes. And to make sure the kids are kept stably placed in whatever setting they are in.